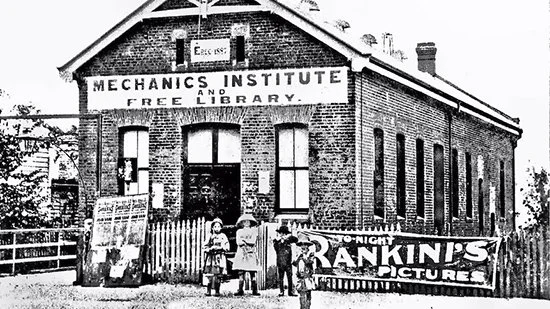

Mechanics’ Institutes: building for culture

(Violet Town Historical Society)

They catch the eye, these sturdy, often impressive 19th century structures, especially in country towns. However, their original use and the ideas behind them are often not immediately evident.

Stefan Petrow, writing in the Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, states the “worthy ideals” of the founders of Australia’s Mechanics’ Institutes as “self-improvement, self-discipline, class co-operation and cultural egalitarianism”. He says these ideals have “long been forgotten”.

He may be right: too often unions and associated organisations for workers are these days associated purely with the pay and conditions of members.

But the movement has always been concerned with the broader wellbeing and education of workers. Last year, we reported in this column on the grand Trades Hall building in Carlton, the ‘People’s Palace’. Though important for union organisation and meetings, it was always meant for “healthy recreation and education for the labouring men…”, as reflected its official name: ‘The Trades Hall and Literary Institute’.

The arts and education were always front of mind.

According to the Victorian History Library (hosted at the Prahran Mechanics Institute) mechanics’ institutes originated with Dr George Birkbeck, who gave a series of free lectures for the working men of Glasgow in 1799.

“At the time, ‘mechanic’ meant artisan, tradesman or working man. The definition became more specific over time, especially during the Industrial Revolution when workers became increasingly associated with machinery.

“The lectures were extremely popular because they were offered free of charge (at a time when formal education had been available only to the wealthy and the clergy) and offered in the evenings (when workers would be able to attend them). These lectures led to facilities dedicated to workers’ education – the Edinburgh School of Arts (1821) and the London Mechanics’ Institute (1823).

“Mechanics’ institutes were established throughout Britain and its colonies including Canada, New Zealand, America, and Australia. In Australia, where they were extremely popular, they had less to do with educating ‘mechanics’ and more to do with providing a model for setting up community facilities and amenities.”

Australia's first mechanics' institute was established in Hobart in 1827 and Petrow says the facilities here “sought to give skilled working men education for life and work, providing lectures, classes, libraries and even museums”.

The Mechanics’ Institutes of Victoria Incorporated (MIV) says its buildings were the precursors of adult education and libraries in Victoria.

“The first Victorian Mechanics' Institute was the Melbourne Mechanics' Institute established in 1839 and renamed The Melbourne Athenaeum in 1873. The Athenaeum continues to operate a library, theatres, and shops in its original building at 188 Collins Street, Melbourne.”

There was clearly an unmet need for cultural outlets for working people. MIV says from the 1850s, Mechanics' Institutes spread throughout Victoria “wherever a hall or library, or a school was needed”.

“Nearly a thousand were built in Victoria and 562 remain today.” Eight are still lending libraries.

MIV says in the past each Mechanics' Institute, Athenaeum, or School of Art was not only the most important centre of adult education in its district, but it was also the area's “hub for social and cultural activities”.

“Nearly every town in Victoria had a mechanics’ institute generally comprised of a hall, library and reading rooms, facilities for games and programs of educational and entertaining activities.”

Stefan Petrow believed most mechanics' institutes failed in their educational aims and became “congenial places of resort for middle-class patrons”, the libraries pandering to “non-demanding tastes”, and says “lectures proved less attractive than musical performances and entertainments of various kinds, such as penny readings”.

There’s a hint of the disapproving patriarch about his harsh judgement, as many of these supposedly inferior activities involved women, who undoubtedly required an outlet as much as working men.

The less ornery MIV believes mechanics’ institutes gradually lost their pre-eminence partly because “local and state governments increasingly provided libraries, education and community spaces”.

Yet today more than 500 mechanics’ institute buildings in Victoria are still used as halls and homes for local organisations. Pre-eminent amongst them are the Meeniyan Hall, now a superb musical venue, the Melbourne Athenaeum, with its lending library and magnificent, intimate theatre and the Lilydale Athenaeum Theatre, currently hosting a comedy by Emma Wood.

These buildings remain priceless gifts to their communities. Less well known, perhaps is that they are monuments to the irrepressible collective social and cultural ambitions of the working class.

To check out your local Mechanics Institute and read more about their history, go to the Mechanics’ Institute Victoria Incorporated site.